Unveiling our chemical origins: the composition of planet-forming disks

Contact Information

Description

Since the discovery of the first exoplanet in 1995 more than 6000 exoplanets have been detected nowadays. This indicates that planet formation is a robust mechanism and nearly every star in our Galaxy should host a system of planets. However, many crucial questions about the origin of planets are still unanswered: How and when planets formed in the Solar System and in extra-solar systems? What is the reason of the huge variety of architectures of extrasolar systems? And what chemical composition do Solar System bodies inherit from their natal environment? The master thesis project is aimed to answer these outstanding questions by studying the planet formation site, i.e. planet-forming disks around young Sun-like stars (i.e. young stars with mass similar to our Sun).

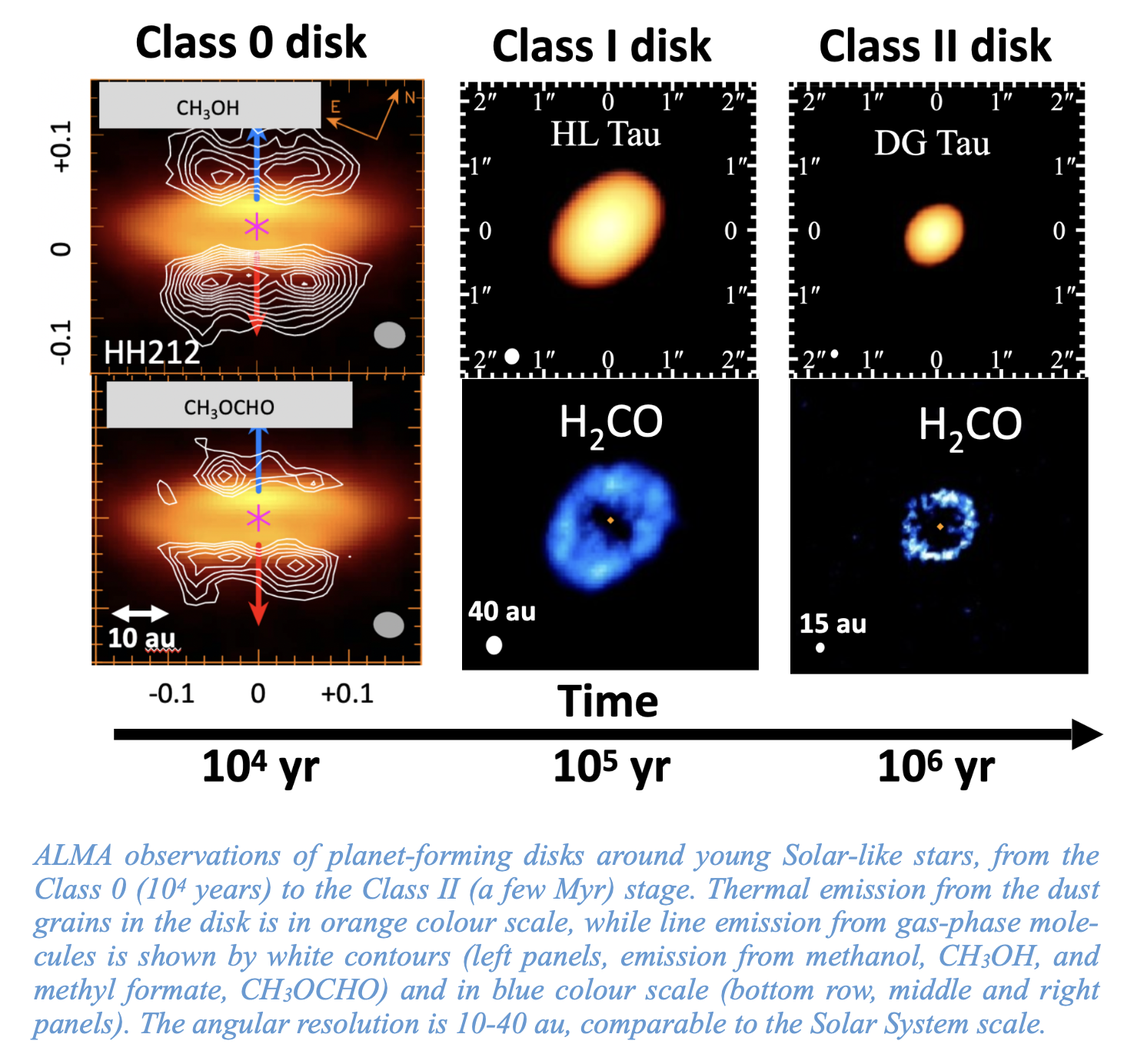

The master student will analyse observations taken with state-of-the-art interferometers working at millimetre and centimetre wavelengths, such as ALMA and VLA, to detect the emission from gaseous molecules and dust grains in planet-forming disks at different stages of evolution (from 104 years to a few Myr) down to scales of a few au, i.e. comparable to the size of our Solar System (50 au) (see as an example the figure below).

The student will use radiative transfer codes to analyse molecular line emission and derive the gas physical conditions and molecular abundances. The spatial distribution and abundance of molecules in disks will be compared with the predictions from thermo-chemical disk models to constrain the formation mechanisms of simple molecules as well as (complex) organics, which are believed to be the building blocks of prebiotic molecules. Finally, the chemical composition of the planet-forming disks will be compared with that observed in comets, which preserve a nearly pristine record of the early Solar System.